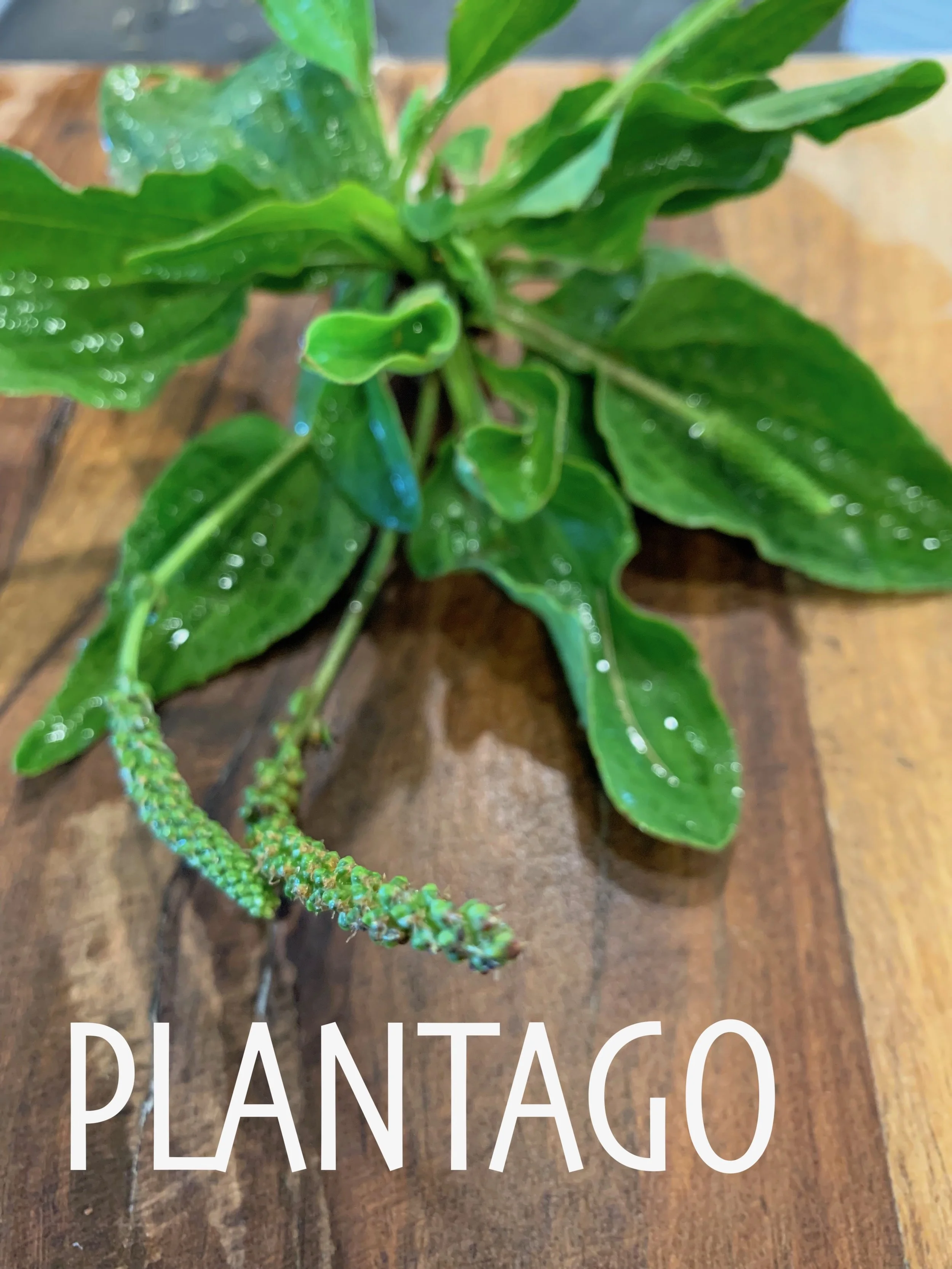

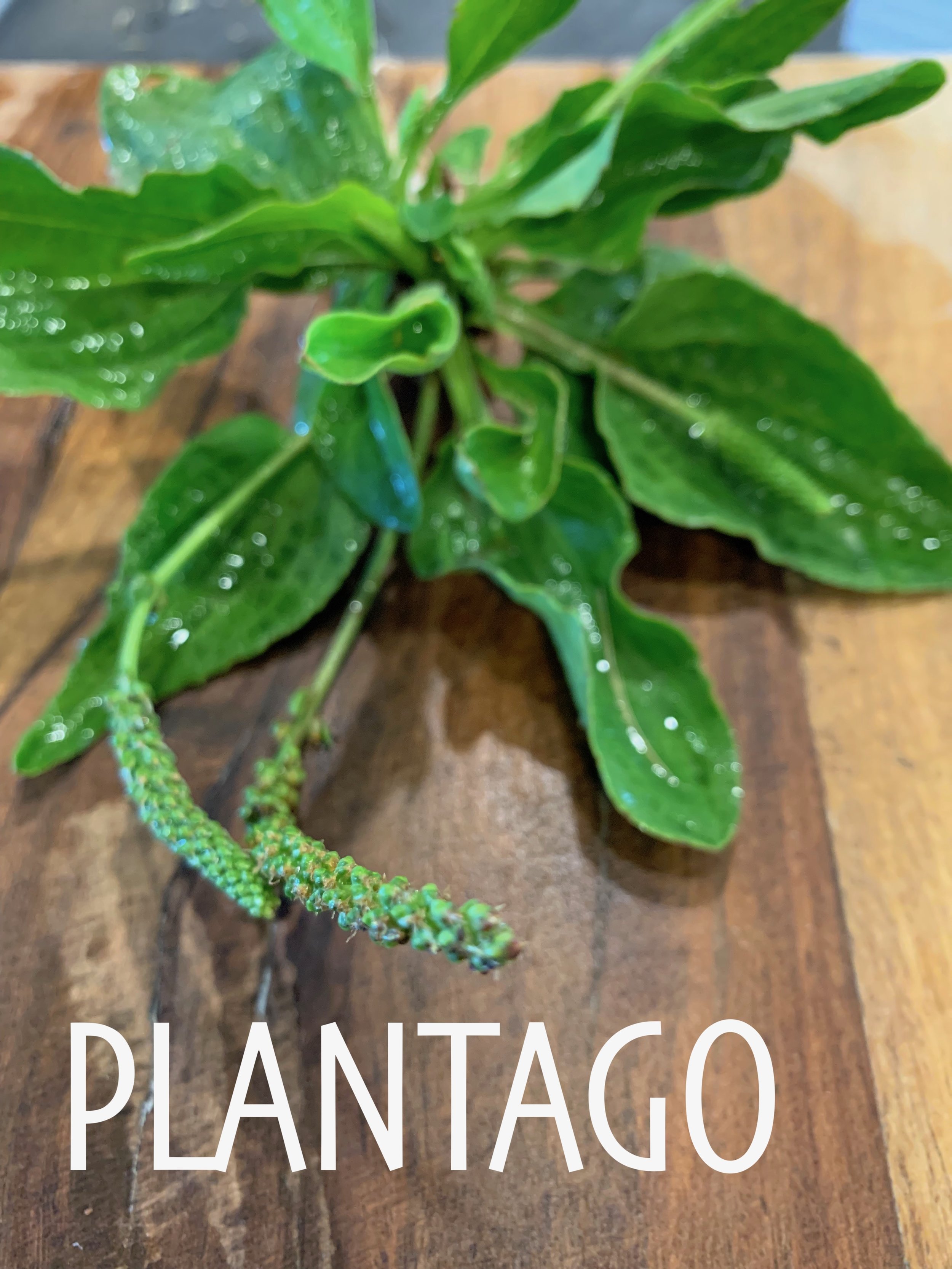

Plantago: Shakespeare, Potions, and One Mad Terrier.

To say “whales are big,” is true. To say, “Jupiter is big,” is also true. However, when a whale is juxtaposed against Jupiter, “big” just doesn’t seem to cut the butter.

Well, Plantago’s use among humans, in relation to most Earthly vegetation, is titanic. It has been used almost universally as a wound healer in traditional medicine by peoples having little to do with each other. This is usually cause for the bell of ethnobotany to sound: “we might have something here!” Unsurprisingly, scientific analysis has supported many traditional uses of plantain.

Plantain is so ingrained in our human culture that it has found its way into the world of countless poets, William Shakespeare’s plays, ancient Chinese legends, and—most assuredly— your backyard garden.

Today we will be exploring the plantain in general terms: its legend, medicinal value, food use, and ethnobotany. However, we will ALSO be doing something extra special today.

By the colloquial power invested in us common folk—regular ole’ humans with heads and stuff— it is time to flex the power of the people and introduce into the Earthling vernacular a new poetic name for the common plantain: PLANTAGO! Say it with me… plant-AH-go.

There are exactly 100 reasons why we are justified in taking this historic step together:

Reason #1: Plantain (banana) and plantago are not related, however, both are commonly called “plantain.”

Reason #2: We are going to explore the plantain banana in the future, and I don’t want to confuse things.

Reason #3-100: See reasons one and two.

Moving on!

This article was inspired by a friend, Ras, who sent a photograph of plantago growing weedy and happily his backyard. Through his intuition—perhaps an empathic connection to forebears plunging backwards into eternity—he suspected this plant was a nutritious green. But instead of ingesting the plant and waiting to see if he died a horrific death (or, at least, spent a considerable amount of time moaning in the bathroom), he decided to do some earnest research.

Be like Ras.

It turns out that our buddy is the accidental farmer of a food and medicine that has clasped the hand of humankind from our toddling origins.

I bet you are too.

Welcome to the ancient, healing, and high-brow-literaturey world of Plantago!

Plantago major: roots and all.

Plantago spp.

with special attention given to Plantago major

Family— Plantaginaceae

Family Characteristics — Plantaginaceae family members appear to have parallel leaf venation, however, these plants actually have strong parallel fibers in their leaves with more inconspicuous netted venation occurring in-between [1]. Yes, Traveller, they are dicots. Further, and most famously, family members have basal leaves and characteristic flower spikes containing corollas with a papery texture [11].

Aliases — common plantain, broadleaf plantain, English plantain, great plantain, Indian wheat, plantain, plantane, plantago, rib grass, ribwort, riplin-grass, ripple-grass, rupple-grass, rybgrasse, rybewurt, path weed, waybread, way-breed, white man’s footprint; 車前 [meaning: plant before the cart] (CHINESE); hontsribbe [meaning: dog-rib](DUTCH); rosripp [meaning: horse-rib](GERMAN); arnoglossos, cynoglossus (GREEK); baartang (HINDI); Healin’ Blade, Healin’ Leaf, Slan-lus [meaning: healing herb], Lus-an-t- slanuehaidh [meaning: healing herb] (IRISH); plantāginem (Latin); sia'sakip'oke'na [meaning: a wide leaf] (MENOMINI); Ceca’ guski’ buge sink [meaning: leaves grow up and also lie flat on the ground], Pakwan, jimuki gobug (OJIBWE); Moomsh (PIMA); Astylletilys, llyriad llwynhidydd, llwyn y neidr, pennau'r gwyr, sowdl Crist [meaning: Christ’s heel], traeturiad y bugeilydd, Ysgelynllys (WELSH)

Binomial Etymology—Plantago and Plantagin were Latin terms for the plant, while major was the Latin term for “larger” [2]. In Latin, Planta, was a word meaning “the sole of the foot. [11]” This is interesting because it has been widely reported (although I haven’t found reference to a specific tribe) that Native Americans called the plant the “white man’s foot print,” while, those the First Peoples would consider to be white, named the plant after the sole of the foot. I am not sure who influenced who in this case. Perhaps you can find out?

Binomial Pronunciation: — According to our buddies, Merriam and Webster, Plantago is pronounced as such: plan-ˈtā-gō [12]. I pronounce it plant-AH-gō… so there.

Toe-māt-oh… tam-AH-toe; plan-ˈtā-gō….plan-TAH-gō… only the most annoying among us will make the correction.

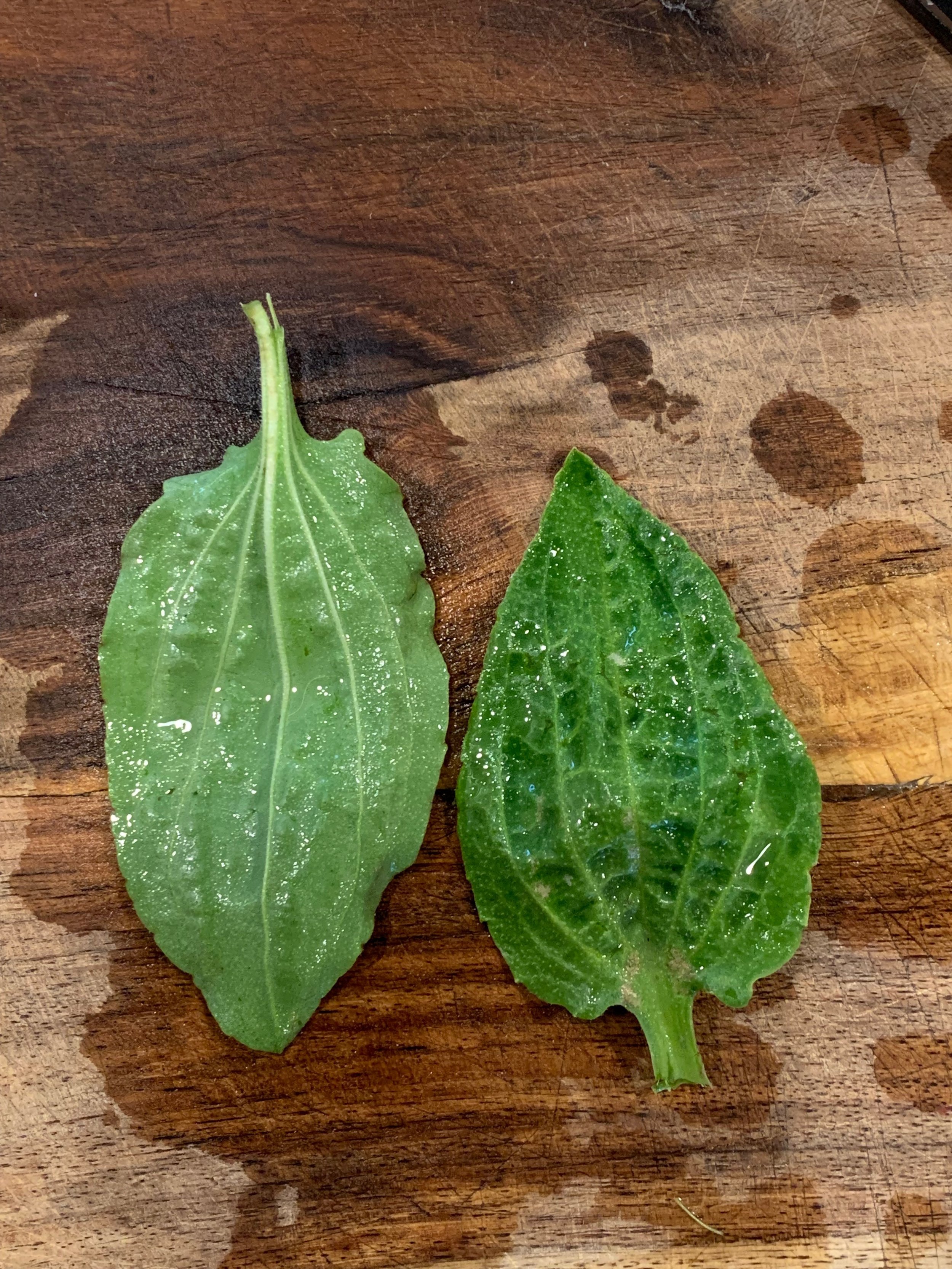

Plantago Description

P. major is a perennial plant with broadly obovate leaves exceeding 1 cm that dramatically narrow near the petiole [11]. P. major, specifically, is considered to be a “cosmopolitan alien” (a respectable band name).

Plantago major in it’s usual condition and habitat: looking sad, chopped up, and squatting in a grass lawn..

Plantago Habitat

Plantago grows in compacted and disturbed soils. It is a common plant-citizen of lawns, parks, and backyards the world over [6].

Specific Warning

Plantago has been shown to bioaccumulate heavy metals in areas of high automobile traffic [25]. It is therefore advised—as always— to be mindful and harvest plants from areas of relatively low pollution.

Plantago Culinary Uses

There is no question, plantago has been utilized as a food for a very long time. An ancient Native American people thriving roughly between 100 and 1300 AD in the four-corners region, the ANASAZI (a Navajo term meaning “ancient enemy”) evidently processed a specie of plantago for food [8].

The young leaves can be used much like spinach, and leaves (both young and old) can be prepared as an herbal tisane.

Plantago lanceolata.

Ethnopharmacology of Plantago

(Medicinal Uses)

Wooo, Lord! If I were able to translate all of the ancient Latin sources discussing the medicinal uses of plantāginem for you, this article would be longer by lightyears. Nevertheless, for millennia, plantago has enjoyed a near universal reverence as a medicine by people and cultures all over our planet.

Plantago Among the British

Brits of the 18th century held that plantago juice with lemon was a “noble diuretic,” and that cutting a piece of the root and placing it in your ear would alleviate a toothache [10]. The ENGLISH of the 17th and 18th century drank plantago juice to allay stomach or bowel trouble, internal bleeding, excessive bleeding during menstruation, lung trouble including coughing, edema, epilepsy, eye inflammation, caligo, and pterygium (in the form of drops), skin inflammation, burns, herpes sores, gout, dog/snake bites, insanity, and to kill parasitic worms in the form of a leaf tea (vermifuge) [16]. Wearing a necklace of plantago roots was said to be a treatment for tuberculosis (known as “the king’s evil) [27].

Plantago Among the Chinese

Plantago was most widely esteemed among the Chinese as a cure for blood in the urine, however, plantago was also used to treat tracheitis, difficulty urinating, vaginal discharge, edema, jaundice, dysentary, pink eye, eye pain, cough, sore throat, and skin abrasions [20].

Plantago Among the French

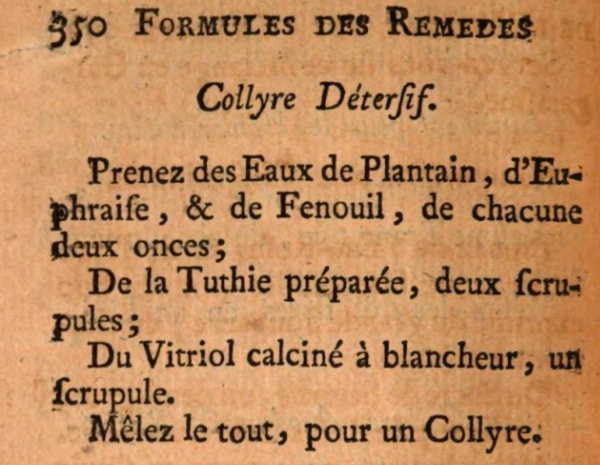

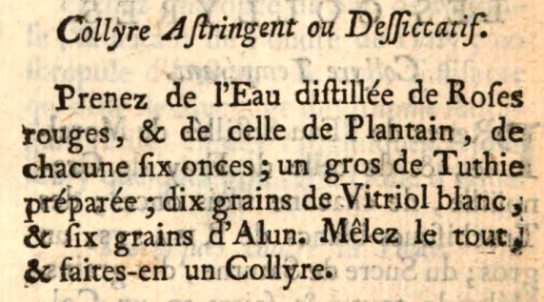

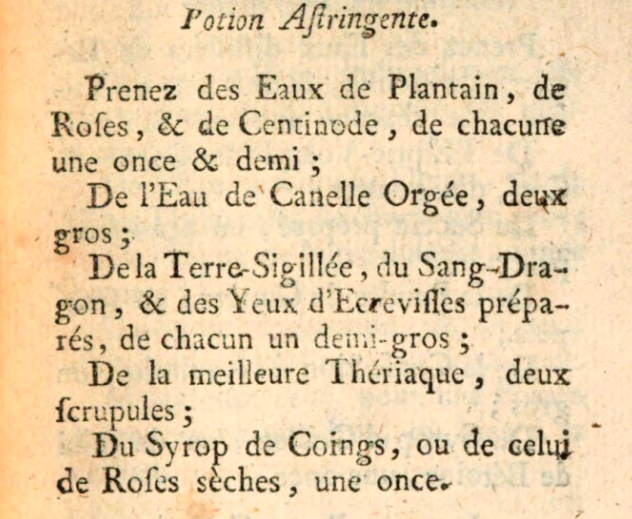

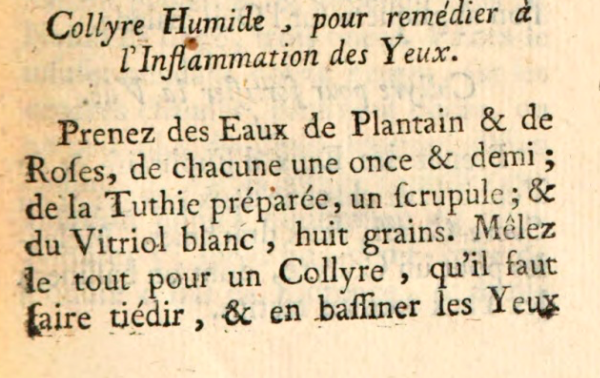

The FRENCH made extensive use of plantago (especially in the form of eye drops) for a myriad of different conditions in the 18th century [13]. I’ll level with you, Traveller; contrary to popular belief, my knowledge of old French is not so good. However, thanks to my buddy, Google Translate, I have gleaned the following information from a 272-year-old remedy cookbook entitled Suite de l'Abbrégé de toute la medecine pratique: seconde partie où tome VII [13]. I will include pictures of the source recipes in a gallery below for your reference— respective of order—so that you may correct potential mistranslations.

The French utilized plantago in a universal potion, eye drops/eye wash, astringent potion, eye drops for inflammation / ulcers of the eyes, and even a potion to combat blood loss. Since plantago was not used alone in these preparations, I will leave you to explore this text on your own.

The 18th century FRENCH further considered plantago to be a great fever reducer, even claiming that two-four ounces of plantago juice had the power to cure a fever (see image below) [14].

[14] Geoffroy, E., Cavelier Le Prieur, G., Desaint, J., Saillant, C., Didot, P. François., Salerne, F., Nobleville, A. de., Escuela de Veterinaria (Madrid)., Desaint et Saillant (París). (1757). Traité de la matière médicale ou Histoire des vertus, du choix et de l'usage des remedes simples. Nouvèlle éd. A Paris: chez Desaint & Saillant .

The FRENCH botanist, Joseph Pitton de Tournefort (1656-1708), whom is credited with elucidating the concept of a botanical genus, also asserted plantago’s ability to break a fever (febrifuge) [15]. Additionally he touted the plant’s efficacy against diarrhea (using 1/8 oz of powdered seed), excess blood loss due to menstruation or hemorrhoids, and as drops to treat eye inflammation [15]. Further, he touts the root’s ability to lend a red dye to paper. Perhaps we could try that? FRENCH women, reportedly used the plant to prevent miscarriage or abortion by mixing plantago seeds with egg or broth during their pregnancy [15].

Plantago Among the Germans

Germans endorsed the use of plantago through their “Commission E,” to treat colds, inflammation (both nasal pharyngeal and skin-related), coughs, and bronchitis [21].

Plantago Among the Ancient Greek

Aristotle (384–322 BC) recommended the use of plantain to aid excessive menstruation, miscarriage, child birth, ergotism, internal bleeding, and infant thrush [17].

Plantago in India

According to the people of INDIA, from the INDIAN Materia Medica, plantago is used to treat insect bites, diarrhea, hemorrhoids, and “blood impurities” [22].

Plantago Among the Irish

In Roscrea, Ireland, in 1796, a “mad terrier” reportedly bit seven people. A tablespoon of plantago juice was given to them (once in the morning and once at night) along with a poultice of the fresh leaves applied directly to the dog bites. One of the victims was reportedly “saved” by this remedy, while the remaining six died. The plantago treatment, however, reportedly cured all of the infamous symptoms of hydrophobia associated with advanced stage rabies [28].

I have reached out to the Tipperary County Council to see if we can learn more about this event. Let’s hope we hear back!

Plantago Among Jamaicans

JAMAICANS used plantago to treat sore eyes by washing them in plantago tea, or baking the leaves and squeezing the juice into their eyes [5].

Plantago Among Native Americans

The CHOCTAW used fresh plantago leaves to treat burns and inflammation [18] .

The MENOMENI would heat the leaves and apply them face-first on tho the skin to reduce inflammation [3].

The OJIBWE used plantago as a soothing topical medicine to treat sores, sprains, burns, bruises, bee-stings, and snakebites by soaking the leaves in warm water and binding them to the afflicted area. In fact, the ethnobotanist, Huron Herbert Smith—author of Ethnobotany of the Ojibwe Indians (1932)—cured his own badly lacerated, infected, and grossly swollen hand in this manner while learning from the Ojibwe [4].

The root was used as a life medicine by the NAVAJO [9].

KIOWA elders would tie plantago to their heads as a wreath and symbol of health [7].

Plantago Among Perso-Arabic Unani Practitioners

UNANI practitioners recognize plantago as effective in the treatment of catarrh (excess mucus buildup in the nose and throat), and inflammation both in the nose and throat and externally [21].

PHWEEEEWWWW!

Plantago major seed heads.

Plantago Pharmaceutical effects

Plantago major has been shown to posses phenolic compounds (the most active being caffeic acid) that have shown promising antiviral properties in a laboratory setting[23].

Plantago major has been shown effective in biosynthesizing silver nanoparticles used in the treatment of breast cancer [24].

An ex-vivo study of plantago extract has shown that ethanol-based extracts show verifiable efficacy in treating and healing wounds [26].

Plantago in Legend

The Chinese colloquial term, 車前, or, Cheqian, comes from a legend going back to the Han Dynasty (206 BC–220 AD). According legend, the Chinese war general, Ma-Wu— who’s soldiers were experiencing hardship and famine—noticed an alarming development in an already dire situation: many soldiers and horses were passing blood with their urine. Not good!

Ma-Wu’s horse groom noticed his horses preferentially munching on plantago. A short while later, the horses were cured. The groom decided to drink plantago tea, and a short while later, he too stopped passing blood with his urine. The groom immediately notified Ma-Wu who decreed that all of his soldiers do the same. A few days later, when all of the soldiers and horses found themselves miraculously cured, Ma-Wu asked the groom where he had found the plant.

The groom answered Ma-Wu, “I found them before the cart.” Thus the Chinese term, 車前, meaning, “plant-before-cart” was born [20].

Plantago in Literature

Mark Akenside (1721-1770)

To spread his careless limbs amid the cool

Of plantane shades, and to the listening deer

The tale of slighted vows and love's disdain

Akenside, M., Barbauld, M. (Anna Letitia). (1795). The pleasures of imagination. London: Printed for T. Cadell, Junior, and W. Davies.

John Armstrong (1709-1779)

Sole Tyrant of the Shade, that long had scap’t The Tanner's rage, ſpoil'd of his callous Rhind, Stands bleak and bare. Theſe, and a thouſand more, Of humbler growth and far inferior Name, Bistort, and Dock, and that way-faring Herb Plantain, her various Forage, boil'd in Wine Yield their aſtringent force…

Armstrong, J. (1739). The oeconomy of love: a poetical essay. The third edition. London: Printed for T. Cooper, at the Globe in Pater-Noster-Row.

Nathaniel Hawthorne (1804-1864)

With no playfulness, as silent as a fish, inactive, Bunny's life passes between a torpid half -slumber and the nibbling of clover tops, lettuce, plantain leaves, pigweed, and crumbs of bread.

Hawthorne, N. (1904). Twenty days with Julian and little Bunny: a diary. New York: Priv. print. [The De Vinne Press].

Rudyard Kipling (1865-1936)

Ah! stud-bred of ill-omen,

I have watched the strongest go—men

Of pith and might and muscle—at your heels, Down the plantain-bordered highway, (Heaven send it ne’er be my way!)

In a lacquered box and jetty upon wheels.

Kipling, R. (1899). The Vampire, and other poems. New York: Street & Smith. (Excerpt from, The Undertaker’s Horse).

Out of dung and horns Dropped in the mire he made a monstrous God, Abhorrent, shapeless, crowned with plantain tufts.

Kipling, R. (1899). The Vampire, and other poems. New York: Street & Smith. (Excerpt from, Evarra and His Gods).

Pallas still mindful of her foe,

(Whilst they did with each fires glow)

Had to the place the Spiders Lar,

Dispath'd before the Ev'nings Star ;

He learned was in Natures Laws,

Of all her foliage knew the cause,

And 'mongst the rest in his choice want

Unplanted had this Plantane plant.

Lovelace, R. (1906). The poems of Richard Lovelace: Lucasta, etc.. London: Hutchinson & co..

William Shakespeare (1564-1616)

William Shakespeare Mentioning Plantago

Palamon: These poor slight sores need not a plantain.

Two Noble Kinsmen, Act I., Sc. 2

[19]

……………………………………………………………….

COSTARD: No enigma, no riddle, no l’envoy; no salve in the mail, sir. O, sir, Plantain, a plain Plantain ; no l'envoy, no l'envoy ; no salve, sir, but a Plantain!

ARMADO: Come hither, come hither, how did this argument begin?

MOTH : By saying that a Costard was broken in a shin. Then call'd you for the l'envoy.

COSTARD: True, and I for a Plantain: thus came your argument in.

Love's Labours Lost, Act III., Sc. 1.

[19]

………………………………………………………………..

BENVOLIO: One desperate grief cures with anothers languish ; Take thou some new infection to thy eye ; And the rank poison of the old will die.

ROMEO: Your Plantain leaf is excellent for that.

BENVOLIO: For what, I pray thee?

ROMEO: For your broken shin.

Romeo and Juliet, Act I., Sc. 2.

[19]

Plantago Nutrition

Plantago lanceolata

Plantain has been found to be rich in vitamins C, A, and K as well as calcium.

To my Patreon supporters, I am eternally grateful! Thank you for your continued support and active encouragement through the trials of life.

If you would like to support this research, be sure to visit: https://www.patreon.com/pullupyourplants

Please comment with any corrections, observations, perspectives, or stories regarding plantago below. All of references are available upon request by emailing me here: pullupyourplants @ gmail.com

With Love,

![[14] Geoffroy, E., Cavelier Le Prieur, G., Desaint, J., Saillant, C., Didot, P. François., Salerne, F., Nobleville, A. de., Escuela de Veterinaria (Madrid)., Desaint et Saillant (París). (1757). Traité de la matière médicale ou Histoire des vertus, …](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/59bae60f1f318d07a99856a4/1561049894615-L3NI0CIZ9QZZTDBHFKFC/Screen+Shot+2019-06-20+at+10.57.26+AM.png)