Purslane: A Vegetable Type of Immortality

Purslane is one of a compound of abundant wild plants typically referred to as quelites, or “wild greens” in Spanish. It grows wherever there is sunshine: cracks in the pavement, asphalt, gardens, junkyards, and (cue the sentimental music)… in our hearts. Well, maybe not.

Purslane is a notorious bane to home farmers. Like a circus performer, precariously balancing dozens of delicate porcelain cups full of seeds, one plant can spill thousands of progeny the moment you disturb, or pull the plant from the ground. Mildly disturb one plant and multitudes will grow in its place. In fact, one plant can produce 240,000 seeds in its life [62].

Before you decide to use the nuclear option (herbicide), ask yourself this: is the presence of purslane in your garden a bad thing? Why has it evolved to handle being picked so well?

Perhaps, it is because we have been pulling up this particular plant… for millennia.

Purslane is popularly considered a “superfood” and is widely touted as the world’s greatest leafy source of Omega 3 fatty acids in the form of Alpha-linolenic Acid (ALA) on Earth [46]. If vegans and vegetarians had incredibly boring dreams, they would dream of this level of nutrition otherwise derived from animals. Purslane is awash in vitamins and minerals. It has been used medicinally for eons by your ancestors. It is a CAM 4 photosynthetic plant so it is suited well for exceedingly hot and dry conditions. Yes, purslane is a food of the past, but it is also may be a food that can survive our future, especially if our future is to include some amount of climatic dystopia.

Also, do you secretly have a neurotic-yet-persistent fear that you just may be riddled with intestinal parasitic worms? Purslane might be able to help you with that. More on that later.

Purslane seeds have been recorded to survive 30 years of storage and 40 years in the Earth [23]. You will never be able to remove them all from your soil… they are legion. Why not learn to appreciate them?

Welcome to the overabundant, underutilized, and hyper-nutritious world of purslane:

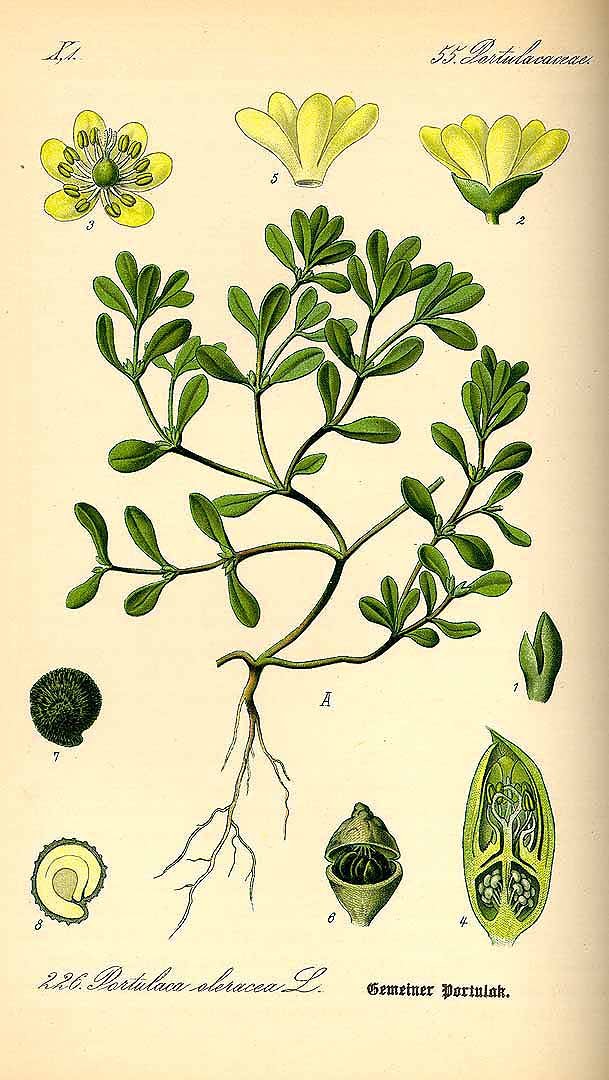

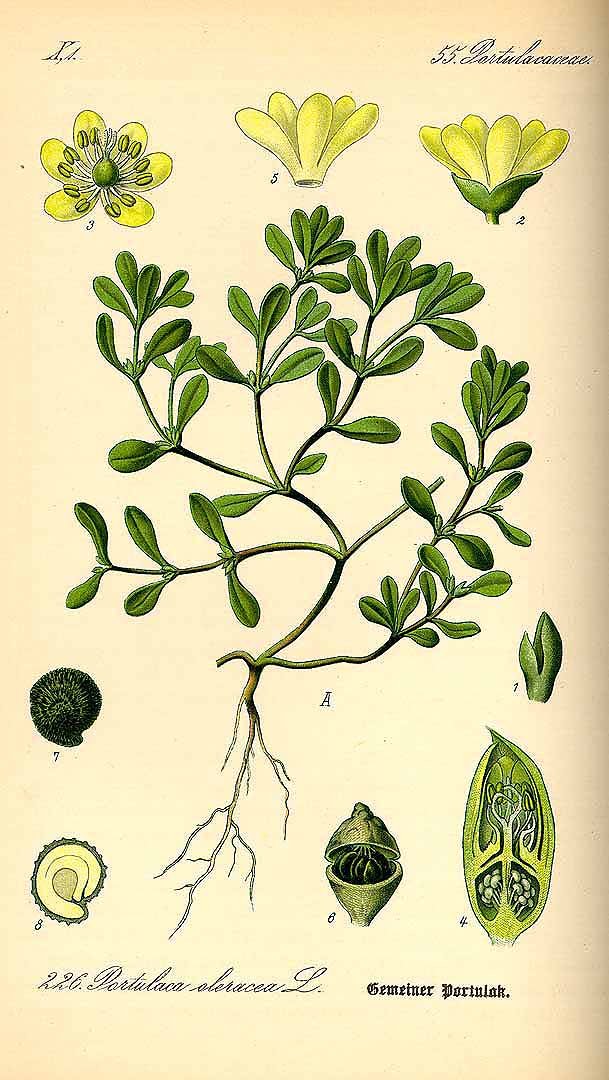

Portulaca oleracea L.

Family — Portulacaceae

Family Characteristics —

Aliases —common portulaca [23], little hooweed [23], low pigweed[23], purslane, pursley [23], pursly [13], pussly[12,13], wild portulac [23], wild portulaca [23](AMERICA-AMERICAN ENGLISH) koohkooša awiilawi [48] (AMERICA-MIAMI TRIBE); Beldroega-branca [39], Bedroégua [39] (BRAZIL-PORTUGUESE); Ma-Chi-Xian-马齿苋[33] (CHINA-MANDARIN); majinsai [43](CHINA-MONGOL HERDSMEN); poupier [5] (FRANCE-FRENCH); Pirtuyakas [16] (ECUADOR-SHUAR); andrakla [3], glustrida [3] (GREECE-GREEK); დანდური (Danduri)(GEORGIA-GEORGIAN)[53]; Pucchiacchella Erva vasciulella (Salernitan dialect) [42](ITALY-VARIOUS) verdolaga (SPANISH); xedxe (Zapotec) [38] (MEXICO-VARIOUS); رجلة, تسمامین-Rujlah, عرجلة-Errejla [60](MOROCCO-IMAZIGHEN); Fasa kasa (HAUSA), papasan (YURUBU) (NIGERIA-VARIOUS)[22]; Lohan [43] (INDIA-PADDARI); Leibak Kundo [55] (INDIA-MEITEI)

“Khursa, Baralaniya, Khulpha (Hindi); Vazhukkaikeerai, Karikeerai, Pulikeerai, Parupukkirai (Tamil); Payalaku, Pedda payili-kura, Ganga pavili-kura, Pappu koora (Telugu); Parunigag, Bada balbaluva (Oria); Bhuigoli, Kurfah, Mhotighol (Marathi); Cheriyagolicheera, Karicheera, Kozhuppa, Kozhuppacheera, Manalcheera, Suvandacheera, Uppucheera (Malayalam)” (INDIA-VARIOUS)[19];

andracla [3], perchiazze [3] porcellana [6] (ITALY-ITALIAN); 소비름-Soebireum [57](KOREA-KOREAN); Sormai [42] (PAKISTAN); Kgobe-di-metsing [28](SOUTH AFRICA-SETSWANA); vordolaga (Catalan)[40];emporretos [5], verdolaga [3], verdulaga [3](Spanish) (SPAIN-VARIOUS) etebire (Obalanga); temizlik otu [59] (TURKEY-TURKISH) ssezira (Luganda)[35] (UGANDA-VARIOUS).

Binomial Etymology — Portu- is a derivative of the Latin, porta (meaning, gate/door/portal) [44]. The species name, oleracea, is a Latin derivative meaning “suitable for food” or “of cultivation” [24]. It is speculated by some that the “gate” part refers to the small capsule-like fruit of the purslane that opens, presenting the seeds.

(My) Binomial Pronunciation: — Poor-chew-lock-uh oler-aye-see-uh

Symbol — POOL

Description

File:6H-diGangi-Purslane-Seed-Pods.jpg. (2023, June 3). Wikimedia Commons. Retrieved 19:58, March 9, 2024 from https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?title=File:6H-diGangi-Purslane-Seed-Pods.jpg&oldid=770189442.

Leaves are succulent and spatulate, meaning, they are rounded at the end but taper, in this case, to a point toward the petiole (the leaf’s stem). Distinctly, all above parts of this plant are hairless (glabrous), and exude no (NONE/ZILCH/ZERO) milky sap. The stems (also hairless) often have an orange-to-reddish blush. The plant’s growth habit is prostrate on the ground like a sprawling spider. The flowers are small, barely visible, and yellow. The fruits look like open capsules full of extremely small, black seeds.

Habitat

This plant is common in gardens, but you will find them sprouting from cracks in the sidewalk, and blacktop. If you had soil in your ears, they would grow there as well provided full sun exposure. They thrive in the heat of summer.

Archaic Medicinal Uses of olde

Note: This section is not a tacit endorsement for eschewing modern medicines in favor of— I don’t know—rubbing crushed purslane on your festering measles boils as an alternative to vaccination. I have no business doling out medical advice because… I am not a doctor (gasp). Although, I HAVE heard that repeatedly slapping yourself on the butt with a bouquet of fresh purslane cures acute gullibility.

Ambiguously Aristotelian 384-322 B.C.E:

Aristotle., Thompson, D. Wentworth., Ross, W. D. (William David)., Smith, J. Alexander. (1910). The works of Aristotle. Oxford: At the Clarendon Press.

While it is arguable as to whether the work, Problemata, is a true work of Aristotle (academics seem to lean toward “probably not”), the text does wrestle with the problem of why purslane and salt is so effective at reducing gum inflammation [4]. They did not worry themselves over if, but why. We can, at least, reasonably glean from purslane’s inclusion in Problemata that purslane was known for this specific medicinal purpose in ancient Greece circa 384-322 B.C.E (when this work was composed). We just can’t say that Aristotle, himself, woke up from a fevered dream demanding answers to this question personally.

The Roman Empire 65 C.E.

CC BY 4.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0>, via Wikimedia Commons https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/8/86/A._C._Celsus%2C_De_medicina_libri_octo%2C_1657_Wellcome_L0040379.jpg

The Roman physician, Aulus Cornelius Celsus’, wrote his De Medicina, 25 B.C.E–50 C.E. In it, he acknowledged purslane’s use as a food, but also as a source of medicine. Specifically, he prescribed purslane’s use as a combatant against bleeding gums (by chewing on the plant), constipation, and use as a diuretic [10].

Dioscorides’ De Materia Medica (literally translated to “The Materials of Medicine”) was composed circa 65 C.E.. It was a proto-scientific work of primarily herbal medicine used widely until the 16th century [8]. YES, in the times before mass publication, this book was in widespread use for roughly 1,500 YEARS. In this compendium, Dioscorides claimed purslane was effective—in combination with goose grease—to treat inflammation and goiters (referred to by Dioscorides as “scrofulous tumours”) [9].

The Islamic Golden Age 600-1200 C.E.

By his contemporaries, Avicenna was known as al-Shaikh alRa’is (the prince of all philosopher’s), but this incarnation of his name is a holdover medieval simplification of the name Abū Ali al-Husain ibn Abdullah ibn Sina. He was also, mercifully, referred to as simply as Ibn Sina [14]. Ibn Sina wrote his Canon of Medicine (Avicenna Arabum medicorum principis) somewhere around 1000 C.E., and it was used as a staple European university medical textbook for hundreds of years [15]. In his Canon of Medicine, Ibn Sina described a teaspoon (dram) of purslane seeds combined with myrrh (presumably applied topically to the nipple) to help with child weening [14]. These were presumably times before simply screaming THAT’S ENOUGH at the baby was discovered.

English Herbals of the Early Modern Period 1450-1800 C.E.

Gerard, J. (1597). The herball, or generall historie of plantes. Printed by Adam Islip, Joice Norton and Richard Whitakers, anno. Retrieved from https://archive.org/details/herballorgeneral00gera/page/520/mode/2up?q=portulaca

Note: Due to many of these sources occurring before the advent of Linnaean nomenclature, ambiguity exists between what contemporary modern medicinal practitioners may have meant by their Middle English derivations of the word, “purslayne.” Some sources may have been referring to Atriplex portulacoides (sea purslane), or our good friend, Portulaca oleracea. I have included John Gerarde’s 1597 herbal due to its inclusion of the above illustration which erases my doubts… the binomial synonym inclusion didn’t hurt either.

Often drawing from Diosorides and good ol’ Pliny the Elder, John Gerarde’s book, “The Herball, or Generall Historie of Plantes" (1597) gives us insight into the variety of ways the English used purslane during the early modern period. According to this work, raw purslane was used in salads with oil and vinegar, and was considered an appetizer. Medicinally, it was considered good for tooth ailments, inflammation, hemorrhoids, and for expelling worms [4]. Can your purslane salad suddenly evacuate your previously unknown/horrific intestinal worm issue? Eat the salad, and you may find out.

The Roman agronomist Columella’s 60-65 C.E. work, De Re Rustica, includes a recipe for making purslane pickles (see recipes section).

Purslane in Music

Columbia

La Verdolaga by Totó La Momposina

Totó is an endearing term used to describe a small person with a big heart, and La Momposina refers to a lady hailing from Santa Cruz de Mompox, Columbia [2]. A name says a lot. In her song, La Verdolaga (translating literally: “The Purslane”), Toto la Momposina is saying while she has been trampled on, and overlooked by a man like one would a weed (purslane), she takes pride in embodying the strength, beauty, and resilience of the plant that was taken for granted. By the sound of it, she comes back stronger and more beautiful than ever: just as a stepped-on purslane plant would.

Since I don’t want to incur the righteous wrath of Totó La Momposina’s by publishing her copyrighted lyrics, I did my best at translating them in the comments section of her video below. Many versions of this song have been made.

Fun fact: this song was sampled by 50Cent: link.

Mexico:

Pedro Infante- La Verdolaga

Pedro Infante was a movie star and musician in the old Ranchero style. In this song, he likens purslane to love itself. In the song he declares that the most beautiful loves are like purslane, in that, you don’t need to give them much for them to grow “like a plague” (Los amores más bonitos, Son como la verdolaga, Nomás le pones tantito, Y crecen como una plaga). This seems to be the moral of the story, as the verses tend to lament the cruelty and untrustworthiness of women in general. Yikes. Another interpretation could be that “money can’t buy love” and if your try that, you will be ruined.

My Spanish chops are not sufficient to pick up all the poetic nuances. I welcome your input in the comments below. There are many versions of this song as it has become a part of the great lexicon of Mexican Ranchero folk music.

Purslane in ethnopharmacology

From Flore médicale Paris :Imprimerie de C.L.F. Panckoucke,1833-1835. biodiversitylibrary.org/page/41878345

ALBANIA:

Purslane is consumed for its nutritive benefits, and also to treat musculoskeletal diseases [41].

AMERICA:

The Cherokee use the plant as an anthelminthic (to expel worms), and use the juice to treat earaches [49]. The Iroquois use the plant as a topical treatment for burns, and bruises [50]. The Keres use the plant to treat diarrhea, and as an antiseptic wash [51]. The Navajo use the plant as an analgesic for pain, including stomachaches [52].

ECUADOR:

While not used extensively in Ecuador, a paper titled "Estudio Etnobotánico de las Plantas Medicinales en la Parroquia San José de Minas, Provincia de Loja" (Ethnobotanical Study of Medicinal Plants in the Parish of San José de Minas, Loja Province) found that 2% of the subjects they interviewed used purslane medicinally for inflammation and as a diuretic medicine [20]. According to another survey carried out around the Murocomba Protective Forest in 2017, the leaves of purslane are applied topically to treat toothache [21].

KENYA:

Traditional herbalists of Kenya use the whole macerated purslane plant is “administered” to treat cancer [27]. Administered is in quotes because there was no mention of how it is administered.

ETHIOPIA:

In the Harla and Dengego valleys of Eastern Ethiopia, purslane is used to relieve constipation [29][36][39], and cough[36]. In the Erer Valley, pastoral communities also use the plant for constipation as well as gastritis, peptic ulcers, and fungal infections [39].

HAITI:

Haitian immigrants to Cuba used the leaves of purslane as a vermifuge to treat intestinal parasites (a use for the plant condoned by Cuba’s own pharmacopeia) [30].

INDIA:

In Southern India, purslane is used to treat mouth wounds, kidney/liver stones, cardiovascular disease, earache, and to expel worms as a vermifuge [56].

ITALY:

People on the Aegadian Islands know of purslane as a vermifuge used to expel worms [58].

IVORY COAST:

Purslane is commonly used by Djimini midwives to facilitate childbirth [34].

KOREA:

An infusion of the plant is taken to treat cancer, and used to treat diarrhea by eating the cooked plant [57].

MOROCCO:

Leaves are cooked and used as a treatment for diabetes.

PAKISTAN:

Purslane is used to treat urinary complaints and cardiovascular disease [32]. The cooked leaves are used as a gynecological aid to treat gonorrhoea [54].

TRINIDAD AND TOBAGO:

The fresh leaves and stems are used as a vermifuge to expel worms [33].

UGANDA:

The leaves are made into a decoction and drank to treat irregular menstruation, and stomachache among Luganda-speaking “indigenous groups” (presumed by me to be the Baganda, but not specified)[35]. The Obalanga consume the cooked shoots for food [37].

Purslane in Ethnopharmacological Study

Powdered purslane seeds were shown, in a very small pilot clinical trial, to normalize the pattern, duration, and volume of menstruation in women suffering from abnormal menstrual bleeding [25].

Purslane in Literature

Literature

“Lord, I confess to when I dine

The pulse is thine-

And all those other bits that be

There placed by Thee.

The worts, the purslain, and the mess

Of water Cress.”

Herrick, R. (1896). The lyric poems of Robert Herrick. London: J.M. Dent.

“I have made a satisfactory dinner, satisfactory on several accounts, simply off a dish of purslane…”

Thoreau, H. D. (1910). Walden: Or, Life in the woods. Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin.

“…the garden patch requires your energy, plus its own; and the more war is waged upon [weeds], the more does it seem to encourage the purslane, which thrives like a freebooter in this sort of warfare.”

Kirkham, S. D. (1908). In the open; intimate studies and appreciations of nature. San Francisco, CA: P. Elder & Company.

“I found in my yard a purslane that was get-

ting in its work before the frost. It was a

new plant, barely three inches long, and

the weather had been windy and raw. But

in a few days it had not merely come out

of the earth; it had lowered, fruited, and

opened the lid of one of its cups, showing

the seed within, black and perfect. It had

crowded into a week the usual life of a

month.”

Skinner, C. M. (1898). Do-nothing days. With illus. by Violet Oakley and Edw.Stratton Holloway. Phildelphia, PA: Lippincott.

What Does Purslane Taste Like?

According to Diosorides in the first century C.E., purslane is “found to be of good juice, clammie, and sommewhat saltish.” [24] I can’t argue with that assessment. The stems are crisp. The juice is somewhat viscid, and salty. In some plants, there can be a pronounced lemony flavor.

What is the Nutritional Profile (Health Benefits) of Purslane?

The leaves and stems of purslane contain a high amounts of polyunsaturated fatty acids including Omega-3, Omega-6, and Alpha-linolenic acid which is a precursor Omega-3 fatty acid most famously found in fish [45]. The National Institute of Health claims “purslane has the highest level of alpha-linolenic which is an omega 3 fatty acid essential for human nutrition compared to any leafy green vegetable” [46]. The plant is an healthy source of potassium, magnesium, calcium, vitamin c, b-complex vitamins, phosphorus, and iron [47].

Recipes From around the world

Note: AI chatbots seemingly do a somewhat good job of translation. For Youtube videos, turn on closed captioning and set the captions to auto-translate into your native language. To not infringe on the work of these home cooks and chefs, I have provided links, and leave translation to you.

Mexico:

File:Flag of Mexico.svg. (2024, March 9). Wikimedia Commons. Retrieved 21:33, March 21, 2024 from https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?title=File:Flag_of_Mexico.svg&oldid=859261310.

The following recipe booklet produced by The Ministry of Economic Development of Mexico City is a treasure trove of Mexican verdolaga recipes that I will be revisiting roughly translated as Recipe Book: Flavor of Mexico City. See the entire SECTION under the heading "Verdolagas.”

Link: RECETARIO: SABOR A CIUDAD DE MÉXICO

Greece:

File:Flag of Greece.svg. (2024, February 1). Wikimedia Commons. Retrieved 21:35, March 21, 2024 from https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?title=File:Flag_of_Greece.svg&oldid=847708014.

File:Flag of India (3-5).svg. (2023, December 24). Wikimedia Commons. Retrieved 21:37, March 21, 2024 from https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?title=File:Flag_of_India_(3-5).svg&oldid=834500714.

कुल्फा साग—KULFA KA SAAG—Purslane Leaves

FRANCE:

File:Flag of France (1794–1815, 1830–1974).svg. (2024, January 31). Wikimedia Commons. Retrieved 21:39, March 21, 2024 from https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?title=File:Flag_of_France_(1794%E2%80%931815,_1830%E2%80%931974).svg&oldid=847590973.

Link: Tarte au Pourpier—Purslane Quiche

Italy:

File:Flag of Italy.svg. (2024, March 21). Wikimedia Commons. Retrieved 21:41, March 21, 2024 from https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?title=File:Flag_of_Italy.svg&oldid=862359419.

Link: Purslane and Pistachio Pesto

TURKEY:

File:Flag of Turkey.svg. (2024, March 12). Wikimedia Commons. Retrieved 21:44, March 21, 2024 from https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?title=File:Flag_of_Turkey.svg&oldid=859878504.

Link: Sarımsaklı Semizotu Salatası Tarifi-Purslane Salad with Garlic

CHINA (ZHUANG ETHNIC GROUP):

File:Flag of the Zhuang people.svg. (2023, May 14). Wikimedia Commons. Retrieved 21:46, March 21, 2024 from https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?title=File:Flag_of_the_Zhuang_people.svg&oldid=762996094.

The Zhuang take fresh purslane, blanch it, chop it up, and flavor it with garlic, sesame oil, and soy sauce to taste [31].

Historic RECIPES for purslane

SCOTLAND 1756:

Reid, J. (1756). The Scots gardiner for the climate of Scotland, in three parts ..: Together with The gardiner's kalendar, The florist's vade-mecum, The practical bee-master, Observations on the weather, and the Earl of Haddington's Treatise on foresttrees. Edinburgh: Printed for J. Reid.

England 1727:

Smith, E. (1750). The compleat housewife: Or, accomplish’d Gentlewoman’s companion. being a collection of upwards of six hundred of the most approved receipts ... with copper plates ... to which is added, a collection of above three hundred family receipts of medicines; ... by E. Smith. Printed for R. Ware, S. Birt, T. Longman, C. Hitch, J. Hodges and 4 others in London.

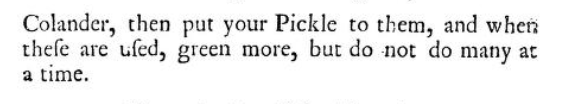

ENGLAND 1753:

The lady’s companion: Containing Three thousand different receipts in every kind of cookery ... (1753). . J. Hodges and R. Baldwin.

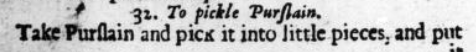

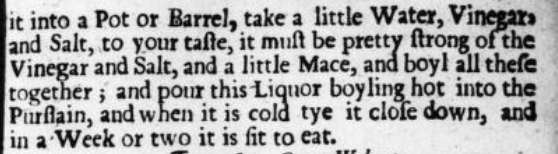

ANCIENT ROME: Pickled Purslane

The Roman agronomist Columella’s 60-65 C.E. work, De Re Rustica, includes a recipe for making purslane pickles.

In the original Latin:

PORTULACA ET BATTIS QUEMADMODUM SERVENTUR.

Hae herbae diligenter purgantur et sub umbra expanduntur, deinde, quarto die, sal in fundis fideliarum substernitur et separatim unaquaeque earum componitur acetoque infuso iterum sal superponitur; nam his herbis muria non convenit. [7]

Translation:

HOW PURSLANE AND BATTIS(?) ARE PRESERVED:

These herbs are carefully cleaned and spread out in the shade. Then, on the fourth day, salt is spread on the bottoms of earthenware jars, and each of the herbs is placed separately in them. Vinegar is poured over them, and salt is added again on top. Brine is not suitable for these herbs.

[61] Turner, W. (1568). The first and seconde partes of the herbal ... lately oversene, corrected and enlarged with the thirde parte: Lately gathered, and Nowe set oute with the names of the herbes, in Greke Latin, English, Duche, Frenche, and in the apothecaries and herbaries Latin, with the properties, degrees, and naturall places of the same.

Poisonous Lookalikes

Below, you will see a picture of spurge (Euphorbia spp.). What differentiates our purslane from common spurge is this: if you break a stem of spurge, you will see a milky-white latex. PURSLANE DOES NOT EXUDE MILKY LATEX.

File:Euphorbia maculata (Creeping Spurge) 1.jpg. (2022, June 2). Wikimedia Commons. Retrieved 21:49, March 21, 2024 from https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?title=File:Euphorbia_maculata_(Creeping_Spurge)_1.jpg&oldid=660914455.

Miscellaneous Anecdotes

In his 1859 book, Plain and Pleasant Talk about Fruits, Flowers, and Farming, the American, Henry Ward Beecher, had a little fun with the myriad of English gardening books carefully describing how to purposefully grow and tend to purslane in the garden:

“ To hear English garden-books speaking of it as “somewhat tender,” of raising it on hot-beds, of drilling it in the open garden, of watering it in dry weather thrice a week, and cutting it carefully so that it may sprout again! Cut it as you please, gentlemen! rake it into alleys, let an August sun scorch it, and if there is so much as a handful of dirt thrown at it, no fear but that it will sprout again. It is a vegetable type of immortality. ”

References

[1] Portulaca L.: Plants of the World Online: Kew Science https://powo.science.kew.org/taxon/urn:lsid:ipni.org:names:325899-2#children

[2] Totó la momposina. New York Latin Culture Magazine®. (2023, January 16). https://www.newyorklatinculture.com/toto-la-momposina/

[3] M. Leonti, S. Nebel, D. Rivera, & M. Heinrich. (2006). Wild Gathered Food Plants in the European Mediterranean: A Comparative Analysis. Economic Botany, 60(2), 130–142. http://www.jstor.org/stable/4257086

[4] Aristotle., Thompson, D. Wentworth., Ross, W. D. (William David)., Smith, J. Alexander. (1910). The works of Aristotle. Oxford: At the Clarendon Press.

[5] Gerard, J. (1597). The herball, or generall historie of plantes. Printed by Adam Islip, Joice Norton and Richard Whitakers, anno. Retrieved from https://archive.org/details/herballorgeneral00gera/page/520/mode/2up?q=portulaca

[6] Jashemski, W. F., Jashemski, S. A., & Meyer, L. N. (1999). A pompeian herbal: Ancient and modern medicinal plants. University of Texas Press. Retrieved from: https://archive.org/details/jashemski-1999-pompeian-herbal/page/81/mode/2up?q=purslane

[7] Columella, L. J. M. (n.d.). Columella: De Re Rustica XII. http://www.thelatinlibrary.com/columella/columella.rr12.shtml

[8] The University of Chicago. (n.d.). Dioscorides: De Materia Medica. Dioscorides: Materia Medica. https://penelope.uchicago.edu/~grout/encyclopaedia_romana/aconite/materiamedica.html

[9] Dioscorides, P. (2000). De Materia Media Being an Herbal with Many Other Medicinal Materials (T. Osbaldeston & R. W. Wood, Trans.). IBIDIS Press. February 5, 2024, https://archive.org/details/Dioscorides_Materia_Medica/page/n303/mode/2up?q=andrachne

[10] Celsus, A. C., & Spencer, W. G. (1935). De Medicina. Harvard University Press. https://archive.org/details/demedicina02celsuoft/page/xlviii/mode/2up?q=purslane

[11] Communications, N. W. (n.d.). Aurelius-Cornelius Celsus. NYU Dentistry. https://dental.nyu.edu/aboutus/rare-book-collection/17-c/aurelius-cornelius.html

[12] MURREY, T. J. (1884). Murray’s salads and sauces. New York. Retrieved from: https://archive.org/details/saladsandsauces00murrgoog/page/n205/mode/2up?q=%22pussly%22

[13] Shands, H. A. (1893). Some pecularities of speech in Mississippi. Norwood Press. https://archive.org/details/cu31924031439015/page/n53/mode/2up?q=%22pussly%22

[14] Avicenna, Abu-Asab, M., Amri, H., & Micozzi, M. S. (2013). Avicenna’s medicine: A new translation of the 11th-century canon with practical applications for Integrative Health Care. Healing Arts Press.

[15] Avicenna’s canon of medicine. galileo. (2017a, January 10). https://galileo.ou.edu/exhibits/avicennas-canon-medicine

[16] Janni, K. D. (2003). Ethnobotany of the shuar of eastern Ecuador. Economic Botany, 57(1), 145–145. https://doi.org/10.1663/0013-0001(2003)057[0145:br]2.0.co;2

[17] Turner, W. (1568, January 1). The first and seconde partes of the herbal-lately oversene... with the thirde parte...also LSO a book of ... baeth, ... 1568 : Turner, William. Internet Archive. https://archive.org/details/bim_early-english-books-1475-1640_the-first-and-seconde-pa_turner-william_1568_0/page/n5/mode/2up?q=poxcelayne

[18] Becker Library Archives and Rare Books. (n.d.). Cordials, unguents, and plasters: Stocking the early modern medicine cabinet. Bernard Becker Medical Library. http://beckerexhibits.wustl.edu/medicine-cabinet/the-basis-of-good-health.html

[19] Portulaca oleracea L. Herbarium JCB. (n.d.). http://flora-peninsula-indica.ces.iisc.ac.in/herbsheet.php?id=8101&cat=7

[20] Coronado Nicolalde, D. M. (2017). Análisis cuantitativo del conocimiento tradicional sobre plantas utilizadas para el tratamiento de enfermedades antitumorales y antiinflamatorias en la Parroquia de San José de Minas, de la Provincia de Pichincha del Cantón Quito. Repositorio Institucional de la UTPL (RiUTPL). https://dspace.utpl.edu.ec/bitstream/123456789/18046/1/Coronado_Nicolalde_Darinka_Marisol.pdf

[21]Bravo Bravo, A. D. (2018). Valoración del uso etnobotánico de plantas medicinales en el área de influencia del bosque protector Murocomba, valencia 2017 (Undergraduate research project). Universidad Técnica Estatal de Quevedo, Facultad de Ciencias Ambientales, Carrera de Ingeniería en Ecoturismo. https://repositorio.uteq.edu.ec/server/api/core/bitstreams/d6f779ec-b698-4f9d-ac60-314146922ef0/content

[22] K.Y. Musa, A. Ahmed, G. Ibrahim, O.E. Ojonugwa, M. Bisalla, H. Musa and U.H. Danmalam, 2007. Toxicity Studies on the Methanolic Extract of Portulaca oleracea L. (Fam. Portulacaceae). Journal of Biological Sciences, 7: 1293-1295.

[23] Cornell University. (n.d.). Common purslane. CALS. https://cals.cornell.edu/weed-science/weed-profiles/common-purslane

[24] Mitich, L. W. (1997). Common purslane (Portulaca oleracea). Weed Technology, 11(2), 394–397. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0890037x00043128

[25] Shobeiri, S. F., Sharei, S., Heidari, A., & Kianbakht, S. (2009). Portulaca oleracea L. in the treatment of patients with abnormal uterine bleeding: A pilot clinical trial. Phytotherapy Research, 23(10), 1411–1414. https://doi.org/10.1002/ptr.2790 https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/ptr.2790

[26] Al-Fatimi, M. (2021). Wild edible plants traditionally collected and used in southern Yemen. Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine, 17(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13002-021-00475-8

[27] Kipkore, W., Wanjohi, B., Rono, H., & Kigen, G. (2014). A study of the medicinal plants used by the Marakwet community in Kenya. Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine, 10(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/1746-4269-10-24

[28] Van der Hoeven, M., Osei, J., Greeff, M., Kruger, A., Faber, M., & Smuts, C. M. (2013). Indigenous and traditional plants: South African parents’ knowledge, perceptions and uses and their children’s sensory acceptance. (Table 3). Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine, 9(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/1746-4269-9-78

[29] Belayneh, A., & Bussa, N. F. (2014). Ethnomedicinal plants used to treat human ailments in the prehistoric place of Harla and dengego valleys, eastern Ethiopia. Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine, 10(1), Table 3. https://doi.org/10.1186/1746-4269-10-18

[30] Volpato, G., Godínez, D., Beyra, A., & Barreto, A. (2009). Uses of medicinal plants by Haitian immigrants and their descendants in the Province of Camagüey, Cuba. Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine, 5(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/1746-4269-5-16

[31] Liu, S., Huang, X., Bin, Z., Yu, B., Lu, Z., Hu, R., & Long, C. (2023). Wild edible plants and their cultural significance among the Zhuang ethnic group in Fangchenggang, Guangxi, China. Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine, 19(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13002-023-00623-2

[32] Akhtar, N., Rashid, A., Murad, W., & Bergmeier, E. (2013a). Diversity and use of ethno-medicinal plants in the region of Swat, North Pakistan. Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine, 9(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/1746-4269-9-25

[33] Lans, C. (2007). Comparison of plants used for skin and stomach problems in Trinidad and Tobago with Asian ethnomedicine. Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine, 3(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/1746-4269-3-3

[34] Koman, S. R., Kpan, W. B., Yao, K., & Ouattara, D. (2021). Medicinal uses of plants by traditional birth attendants to facilitate childbirth among Djimini women in Dabakala (center-north of Côte d’Ivoire). Ethnobotany Research and Applications, 21. https://doi.org/10.32859/era.21.23.1-12

[35] Tugume, P., Kakudidi, E. K., Buyinza, M., Namaalwa, J., Kamatenesi, M., Mucunguzi, P., & Kalema, J. (2016). Ethnobotanical survey of medicinal plant species used by communities around Mabira Central Forest Reserve, Uganda. Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine, 12(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13002-015-0077-4

[36] Belayneh, A., & Bussa, N. F. (2014a). Ethnomedicinal plants used to treat human ailments in the prehistoric place of Harla and dengego valleys, eastern Ethiopia. Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine, 10(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/1746-4269-10-18

[37] Ojelel, S., & Kakudidi, E. K. (2015). Wild edible plant species utilized by a subsistence farming community in Obalanga sub-county, Amuria District, Uganda. Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine, 11(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/1746-4269-11-7

[38] Saynes-Vásquez, A., Caballero, J., Meave, J. A., & Chiang, F. (2013). Cultural change and loss of ethnoecological knowledge among the Isthmus Zapotecs of Mexico. Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine, 9(1), Table 2. https://doi.org/10.1186/1746-4269-9-40

[39] Belayneh, A., Asfaw, Z., Demissew, S., & Bussa, N. F. (2012). Medicinal plants potential and use by pastoral and agro-pastoral communities in Erer Valley of Babile Wereda, Eastern Ethiopia. Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine, 8(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/1746-4269-8-42

[40] Marín, J., Garnatje, T., & Vallès, J. (2023). Traditional knowledge 10 min far from Barcelona: Ethnobotanical Study in the Llobregat River Delta (Catalonia, Ne Iberian Peninsula), a heavily anthropized agricultural area. Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine, 19(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13002-023-00615-2

[41]AbouZid, S. F., & Mohamed, A. A. (2011). Survey on medicinal plants and spices used in Beni-sueif, Upper Egypt. Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine, 7(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/1746-4269-7-18

[42] Ullah, H., Qureshi, R., Munazir, M., Bibi, Y., Saboor, A., Imran, M., Maqsood, M., & Ali, S. (2023). Quantitative ethnobotanical appraisal of Shawal Valley, South Waziristan, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan. Ethnobotany Research and Applications, 25. https://doi.org/10.32859/era.25.527.1-17

[43]Soyolt, Galsannorbu, Yongping, Wunenbayar, Liu, G., & Khasbagan. (2013). Wild plant folk nomenclature of the Mongol herdsmen in the Arhorchin National Nature Reserve, Inner Mongolia, PR China. Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine, 9(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/1746-4269-9-30

[44] Nybakken, O. E. (1959). Greek and Latin in scientific terminology. Iowa State University Press.

[45] Ramos, E. (2023, February 20). The Power of Plants: Purslanes. Magaram Center Nutrition Experts Blog. https://blogs.csun.edu/nutritionexperts/2023/02/20/the-power-of-plants-purslanes/

[46]Uddin, Md. K., Juraimi, A. S., Hossain, M. S., Nahar, Most. A., Ali, Md. E., & Rahman, M. M. (2014). Purslane weed (Portulaca oleracea): A prospective plant source of nutrition, omega-3 fatty acid, and antioxidant attributes. The Scientific World Journal, 2014, 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1155/2014/951019

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3934766/#:~:text=Purslane%20has%20the%20highest%20level,%2Dlinolenic%20acid%20(ALA).

[47] Food Data Central Search Results. USDA. (n.d.). https://fdc.nal.usda.gov/fdc-app.html#/food-details/169274/nutrients

[48] Brian C. (2003). The ethnobotany of the Miami tribe: Traditional plant use ... https://etd.ohiolink.edu/acprod/odb_etd/ws/send_file/send?accession=muhonors1110917365&disposition=inline

[49] Hamel, Paul B. and Mary U. Chiltoskey, 1975, Cherokee Plants and Their Uses -- A 400 Year History, Sylva, N.C. Herald Publishing Co., page 51

[50] Herrick, James William, 1977, Iroquois Medical Botany, State University of New York, Albany, PhD Thesis, page 318

[51] Swank, George R., 1932, The Ethnobotany of the Acoma and Laguna Indians, University of New Mexico, M.A. Thesis, page 62

[52] Elmore, Francis H., 1944, Ethnobotany of the Navajo, Sante Fe, NM. School of American Research, page 97

[53] პანიაგუა სამბრანა. (2020). Მცენარეები კურორტზე – სამკურნალო მცენარეების ბაზარი ბორჯომში. Ethnobotany Research and Applications, 19. https://doi.org/10.32859/era.19.06.1-11

[54]Jan, H. A., Jan, S., Bussmann, R. W., Ahmad, L., Wali, S., & Ahmad, N. (2020). Ethnomedicinal survey of the plants used for gynecological disorders by the indigenous community of District Buner, Pakistan. Ethnobotany Research and Applications, 19. https://doi.org/10.32859/era.19.26.1-18

[55] Meitei, L. R., De, A., & Mao, A. A. (2022). An ethnobotanical study on the wild edible plants used by forest dwellers in Yangoupokpi lokchao wildlife sanctuary, Manipur, India. Ethnobotany Research and Applications, 23. https://doi.org/10.32859/era.23.15.1-25

[56] Santosh Kumar, J., Krishna Chaitanya, M., Semotiuk, A. J., & Krishna, V. (2019). Indigenous knowledge of medicinal plants used by ethnic communities of South India. Ethnobotany Research and Applications, 18. https://doi.org/10.32859/era.18.4.1-112

[57]Song, M.-J., Kim, H., Lee, B.-Y., Brian, H., Park, C.-H., & Hyun, C.-W. (2014). Analysis of traditional knowledge of medicinal plants from residents in Gayasan National Park (Korea). Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine, 10(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/1746-4269-10-74

[58]La Rosa, A., Cornara, L., Saitta, A., Salam, A. M., Grammatico, S., Caputo, M., La Mantia, T., & Quave, C. L. (2021). Ethnobotany of the aegadian islands: Safeguarding biocultural refugia in the Mediterranean. Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine, 17(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13002-021-00470-z

[59] Arı, S., Temel, M., Kargıoğlu, M., & Konuk, M. (2015). Ethnobotanical Survey of plants used in Afyonkarahisar-Turkey. Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine, 11(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13002-015-0067-6

[60] Aboukhalaf, A., Tbatou, M., Kalili, A., Naciri, K., Moujabbir, S., Sahel, K., Rocha, J. M., & Belahsen, R. (2022). Traditional knowledge and use of wild edible plants in Sidi Bennour region (central Morocco). Ethnobotany Research and Applications, 23. https://doi.org/10.32859/era.23.11.1-18

[61] Turner, W. (1568). The first and seconde partes of the herbal ... lately oversene, corrected and enlarged with the thirde parte: Lately gathered, and Nowe set oute with the names of the herbes, in Greke Latin, English, Duche, Frenche, and in the apothecaries and herbaries Latin, with the properties, degrees, and naturall places of the same.

[62] How to manage pests: Common Purslane. UC IPM Online. (n.d.). https://ipm.ucanr.edu/PMG/PESTNOTES/pn7461.html